[ad_1]

There’s an increasing abundance of skittishness surrounding the future of East and Gulf Coast ports.

The labor contract between the International Longshoremen’s Association and the United States Maritime Alliance (USMX) is set to expire at the end of September. The ILA represents some 70,000 dockworkers, while the USMX represents employers at 36 coastal ports — including three of the U.S.’s five busiest ports: the Port of New York and New Jersey, the Port of Savannah, Georgia, and the Port of Houston.

Contract negotiations between the ILA and the USMX began in February 2023 but quickly foundered on the issue of wage increases. Developments since then have not been promising.

‘Talk of potential disruptions has increased’

In November, ILA leadership warned roughly 45,000 of its members to “prepare for the possibility of a coastwide strike in October 2024,” after the current master contract expires. ILA President Harold Daggett also cautioned that there is no chance of extending the current contract past the expiration date.

In other words, ILA dockworkers are fully prepared to swap pallet jacks for picket signs come Oct. 1.

Unsurprisingly, these threats unnerved trade associations like the National Retail Federation, which have actively voiced their desire to facilitate negotiations between the two parties. NRF President and CEO Matthew Shay, in a January letter, expressed concern “that the discussions have been on hold for months and talk of potential disruptions has increased.

“Even the threat of a disruption can have a negative economic impact on the covered ports,” Shay argued, “especially if cargo owners and other supply chain stakeholders believe that operations will be slowed or shut down during the all-important peak shipping season this fall.”

Other analysts concur: In a November post on LinkedIn, Vespucci Maritime CEO Lars Jensen wrote, “[T]he mere threat of a strike could cause shippers to pre-emptively move cargo to the West Coast. … The threat is likely not idle at all, but saber-rattling at this point is to be expected.”

In many ways, the ILA is riding on the numerous successes that labor had in recent years. In August, the Teamsters celebrated the ratification of a new agreement with UPS (albeit one with unintended side effects). After a 46-day strike against Ford, Stellantis and General Motors, the United Auto Workers union secured large pay raises and other benefits for its members last fall.

And, of course, there were the protracted negotiations around West Coast ports.

Shifting tides

Near the peak of the post-COVID import boom, the labor contract between the International Longshore and Warehouse Union (ILWU) and the Pacific Maritime Association (PMA) expired on July 1, 2022. What followed was an 11-month period of confusion, uncertainty and chaos for West Coast importers.

Soon after the contract’s expiration, 52 trade associations, industry organizations and businesses — including the NRF and PMA — penned a letter to California Gov. Gavin Newsom, urging him to incentivize growth at the state’s ports. The letter made the case that, despite the overwhelming growth in total volumes, West Coast ports’ market share had declined 19.4% since 2006 relative to their East and Gulf Coast counterparts.

Newsom was not the only one called on to intervene: More than 150 business groups implored the Biden administration to pressure the ILWU and PMA for a temporary extension of the labor contract, fearing work stoppages and shipment delays.

But while no such extension ever materialized, neither did the stoppages and delays — for a time, that is.

Even with the ILWU’s forbearance from striking, the West Coast ports’ market share continued to erode as shippers would settle for nothing less than a signed deal. Still, the ports were optimistic that volume would return once the negotiations were resolved.

Others were skeptical. “I think a lot of the transition from the West Coast to the East Coast is permanent,” Nerijus Poskus, vice president of ocean strategy at Flexport, told FreightWaves in February 2023. “People have gotten used to this new reality. I don’t think this has much to do with the risk of a strike on the West Coast anymore. I don’t see the West Coast gaining all its share back.”

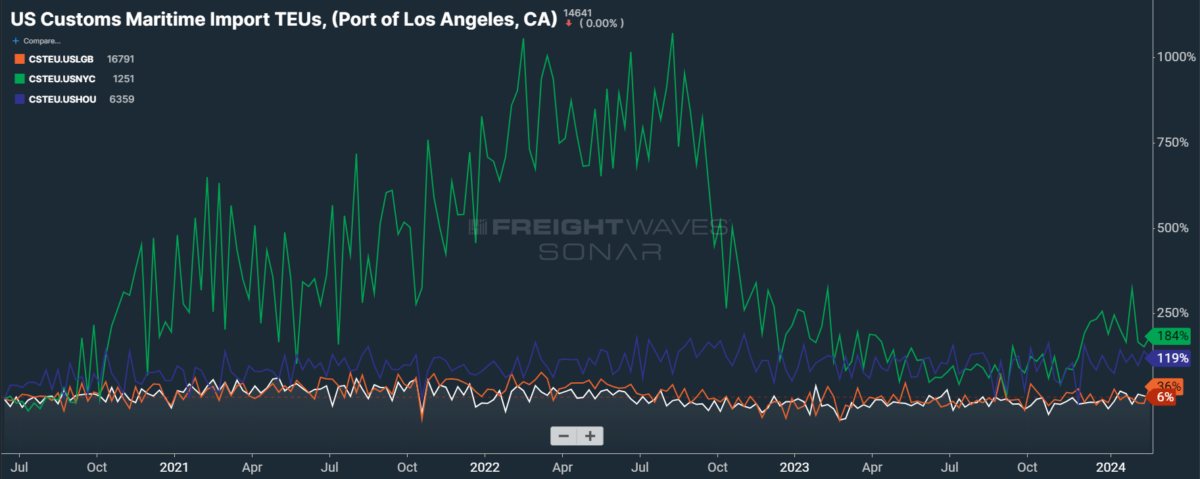

SONAR: CSTEU.USLAX (white), CSTEU.USLGB (orange), CSTEU.USNYC (green) and CSTEU.USHOU (blue)

The bearish case ultimately proved prescient when the ILWU shut down operations at the ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach for 24 hours in April 2023. By the time the stoppage occurred, East and Gulf Coast ports had been outperforming West Coast ports for 23 consecutive months. The following months saw a handful of work stoppages and slowdowns that further eroded shippers’ confidence in the ports’ operational capabilities.

When the ink dried on the final labor contract — nearly a full year after the previous one expired — the damage had already been done.

Extenuating circumstances

Since the resolution of its labor uncertainty, the West Coast has managed to claw back some market share, albeit in efforts aided by circumstances beyond its control. Still, the nature of its struggle can offer an indication of how things might progress along the East and Gulf coasts.

But while there is good reason to believe that a potential ILA strike will impact East and Gulf Coast ports in much the same way as the ILWU affected ones along the West Coast, it also seems as though the ILA is operating from a different playbook.

For one, the ILA has already taken a hard-line stance against continuing operations without a contract in place. Ports represented by the USMX are already in a fragile state, with imports threatened by the continued drought at the Panama Canal. Taken together, these circumstances imply that any ILA stoppages would be swift and its effects immediate, unlike the extended drama that played out along the West Coast.

This inference is strengthened by the fact that imports to East and Gulf Coast ports come from a more diverse mix of origins than the West Coast. Whereas the West Coast primarily gets its cargo from Asia, East and Gulf Coast ports get shipments from Europe and South America as well as Asia.

The ILA also views itself as having a firmer stance against automation than the ILWU, targeting shipping lines directly. “If foreign-owned companies like Maersk and MSC try to replace our jobs with automation,” ILA President Daggett said in November, “they are going to get a painful reminder that longshore workers brought these companies to where they are today.”

Speaking on APM’s Pier 400 terminal at the Port of Los Angeles, Daggett added, “Who the hell is a foreign company like Maersk to come to America and build a fully automated terminal like the one we just saw? Those are jobs lost in America and profits sent back to Copenhagen.”

Maersk, meanwhile, is contending with its own financial challenges after the pandemic-era boom. With ports and shipping lines alike in a bind, the ILA finds itself in a favorable position to push its demands.

For their part, retailers are broadly expected to pull forward their peak season freight so as to avoid potential issues come October. But if negotiations between the ILA and USMX deteriorate further — and especially if the ILA follows through with its first coastwide strike since 1977 — the pendulum is likely to swing back in favor of the West Coast.

[ad_2]

Source link